Histoire du Moulin

The story of the last miller in the mill

To go further…

XIV – The Camandoule Mill

Fifty years ago, I was twenty and I was entering the workforce.

A curious expression that “entering the workforce” is as if before the age of twenty I had never done anything. My first real memories, those that remain engraved in the memory, I really have them from the age of six, that is to say since the occupation of Paris by the German army and I can say that from six to twenty years old, for an inactive person, I can tell stories about them. Here is the one I promised you.

I once told you that I had always been interested in mills, whether they were towers, candlesticks or caviers, whether they were powered by water or wind. That is not entirely accurate, I became interested in them after having operated one for a few years. It was fascinating.

So I was twenty years old. This happened in Provence, in the Haut Var between Draguignan and Grasse, in Fayence to be precise. The village was perched – I suppose it still is – on top of a hill overlooking a plain where roses, jasmine, lavender for the perfumeries of Grasse, and vines were grown. The olive trees grew on “restanques”, delimited by dry stone walls that were built in tiers, up to the top of the hill.

Fayence is a pretty Provencal village with its large square refreshed by the foliage of the plane trees. The old people would gather there in the evening to play pastis and pétanque. There was a restaurant, a grocery store that was a bazaar, a butcher who cooked caillette wonderfully, a bakery where the morning fougasse barely out of the oven melted in your mouth.

Fifty years ago, life was pleasant in this little Provencal village.

Its name comes from a Latin name meaning pleasant place. I went back there about twenty years ago to show my son this place where I had lived and which I had told him so much about. I had trouble recognizing the place, so what it must be like now, I dare not imagine.

Taking the road at the foot of the hill, towards Seillans, there was still, when I went there last time, a dirt track that wound across the plain and died down when it came up against an abandoned chapel. A hundred and fifty meters from its start, on the left, a path planted with mulberry trees led to a property bordered by a river.

The river is called the Camandre, the property the Moulin de Camandoule.

This name alone evokes all the scents of Provence, a subtle blend of thyme, rosemary, lavender, aioli and olive oil.

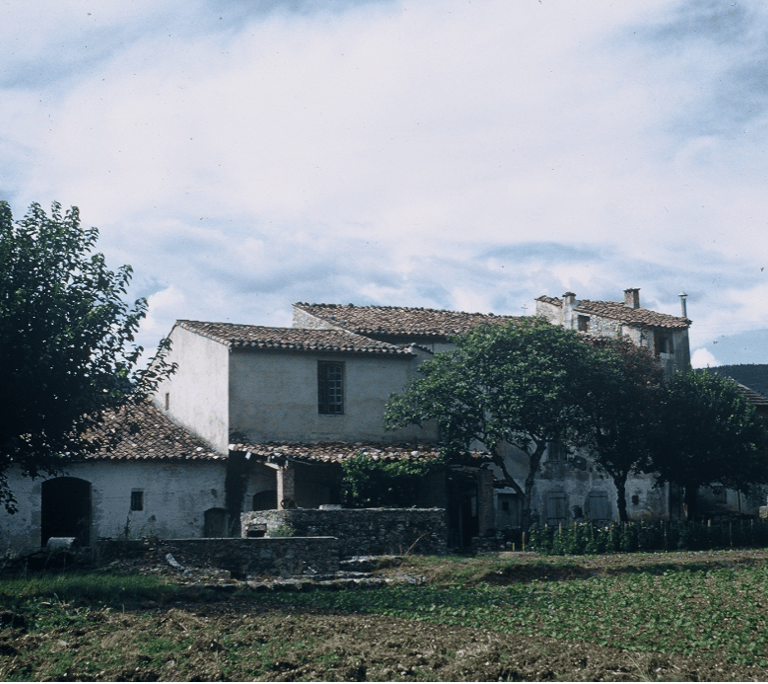

The mulberry tree avenue ended at an aqueduct that was supposedly Roman. Passing under one of its arches, one found oneself in front of the entrance to the house, a real Provençal farmhouse with a ground floor and an upper floor. A tower with a single-sloped roof flanked the right side of the dwelling. Like all old Provençal houses, the main façade faced south. The narrow windows were fitted with shutters to protect against the sun in summer and the cold in winter because, make no mistake, winters can be harsh in Haute Provence. The façade to the north was blind to protect itself, especially during the harsh months, from the freezing mistral. To the north, the façade was higher than that to the south and, as a result, the roof had only one slope.

In front of the house, a fairly large basin protected from the sun by an old mulberry tree, was used to water the vegetable garden going down to the river, lined with poplars.

The house was extended by various buildings. At the Camandoule mill, olive oil was made.

In fact, there were two mills.

The main mill was next to the farmhouse. There, olives were crushed from which the best oil was extracted. Hidden in a high and narrow space, an imposing paddle wheel collected the water brought by the aqueduct and allowed the mechanisms of the mills to be set in motion.

In the other mill, lower quality oils were processed.

Inside, the main mill was remarkable. You would think you had been transported centuries back in time. Upon entering, your gaze stumbled upon an enormous granite stone that turned, around a thick oak beam, in a vat whose bottom was covered with glazed tiles.

Opposite, nestled in stone alcoves, were three large wooden presses under which were piled curious flat raffia cakes that looked like doormats, the scourtins.

At the back of the mill, a stone vat, a sort of gigantic kettle, surmounted an open hearth where there were still ashes from the last fire that had been lit to heat the water.

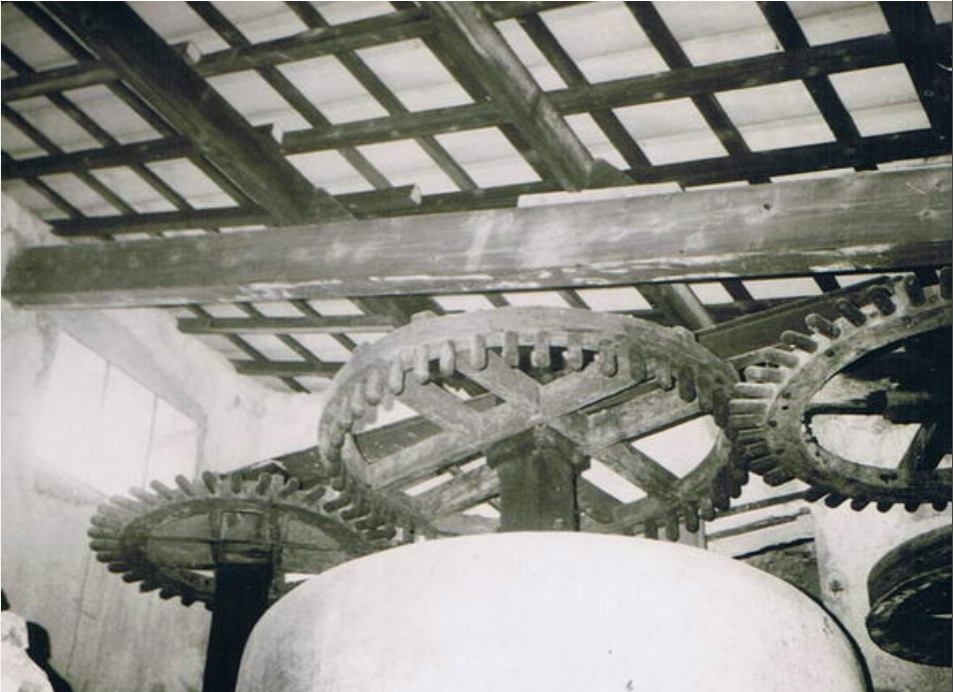

All this was dominated by a clever mechanism of wooden cogwheels, levers and leather belts to operate the wheel to crush the olives and then press them to extract the oil.

On the poorly paved ground, a jumble of cans and pot-bellied sandstone jars, some of which were very old and would have delighted antique dealers. The other mill was identical but smaller and, although it had not worked for a long time, there was still a sickening smell of rancid oil floating in it.

At the Moulin de Camandoule the buildings were in poor condition. Around it, there were four hectares including a vineyard, which was fallow, but the whole thing had a crazy charm. I never stopped bringing it back to life.

In the fall of 1954, I moved to the Moulin de Camandoule, with a good dose of recklessness but a faith that could move mountains.

I had two worries: The first, in chronological order, was to plant fruit trees on the entire land. It was easy for me, it was in an area that I knew.

My second worry, in fact the first in importance, was to revive the mill and there, I entered a totally unknown world. I shared my problem right and left in the village and I was advised to see a certain Arnéodo who had worked at the mill. He had the reputation of knowing his job very well but of having a pig's character.

I met Arnéodo at the Moulin de Camandoule. From what I had gathered from my conversations with the villagers, the mill, while he was working there, had a very good reputation, but he had had a fight with the previous owner, an old crook, and he left overnight. The old crook tried to find other workers, but it didn't work out and the mill closed. Arnéodo confirmed what I already knew.

During our conversation, I explained to him that I was looking for a permanent man to help me develop the land and run the mill because I didn't know anything about it. He looked at me for a moment without saying anything. Then he decided: "If I accept, I want to be the boss for the oil season. In the mill, I'm the one in charge."

We agreed on this question, which was essential for him, the rest was no problem.

It was difficult to give Arnéodo an age, between fifty and sixty perhaps. For a Provençal, he was tall, as tall as me with cold blue eyes. He rolled his cigarettes with grey tobacco wrapped in corn paper. The cigarette butt that he constantly relighted did not leave his lower lip even when he spoke, or rather when he grumbled. His moustache was yellowed by the corn paper and burnt by the too strong flame of his storm lighter. A cap riveted to his head, a flannel belt, grey striped trousers and a waistcoat completed his outfit. I never saw him otherwise.

From September to the end of November, the work consisted of clearing the fallow land, harvesting the few grapes on the vines and taking them to the wine cooperative in exchange for a piquette that was wine in name only. The state gave a bonus (yes, already!) to remove uninteresting vineyards and replace them with apple trees. Pulling up the vines, plowing, clearing the land and planting apple trees kept us busy until the beginning of winter.

Arneodo worked conscientiously but without enthusiasm. I could clearly sense that he was impatient to start the olive season. For my part, I could only be satisfied with my worker’s behavior. The only thing that bothered me was mealtimes; we ate them together like two old bachelors (it was stipulated in our agreements that he was to be fed and housed).

His conversation, which was limited to a few grunts, was not what I would call stimulating. My only reason for satisfaction was to see him remove his eternal corn-paper cigarette from his lower lip; he had not found a way to keep it while eating.

I knew nothing about Arneodo’s private life. Once or twice I tried to extract some clues from him, but I came up against the coldness of his blue eyes and gave up.

On Saturdays, at the end of the work week, he would put on clean clothes, go up to the village to get a shave (at that time, hairdressers also acted as barbers) and spend his evening playing belote.

Sometimes, on Sundays, he would tell me that he had to go see a sister in Draguignan and that he would not return until Monday morning.

When he returned, I did not dare ask him about his sister. Was she really his sister? Perhaps he had a mistress whom he honored from time to time with a visit; I do not believe so because of the position of the corn paper cigarette butt firmly placed on his lower lip.

At the beginning of December, Arnéodo declared that it was time to put the mill in order and to make the rounds of the farmers to announce its reopening. We began our journey on the roads of the Haut Var. The old Provençal peasants looked at the young man, me in this case, with suspicion. He looked like a kid and then he had no accent or more precisely he had the pointed accent of the Parisians, which was worse. But they knew Father Arneodo well and, in general, they confirmed that they would bring their harvest to the mill.

At that time, the vine and the olive tree were the main source of income for the peasants, and I was glad I had hired Arneodo because, without him, it was obvious that no one would have come to bring me their olives.

In mid-January, the olive harvest began. It was fascinating to see the mill in action. I saw that Arneodo's reputation was well deserved. At five in the morning he would get up, light the fire under the water tank, check the condition of the belts and connect the water to set the enormous paddle wheel in motion.

From seven in the morning, the peasants would arrive with their loads of olives piled in jute sacks that were immediately emptied into the tank where the heavy granite stone was located. Arnéodo started the mechanism, the grinding began. The mill filled first with the sound of the pits broken by the millstone and then slowly the scent of the crushed fruits tickled the nostrils. It was the sun and the good mood that penetrated into the mill.

This first operation produced a little oil that fell into a large barrel filled with water under the vat.

When he considered that the quantity of oil floating on the surface of the barrel was sufficient, Arnéodo would delicately collect it on a sort of rimless pan and pour it separately into a can.

It was by this very delicate operation that the skill of the worker was judged because there was no question of mixing the oil and water and even at the end when the oily film was very thin, Arnéodo managed to collect it without the slightest drop of water. The millstone passed and repassed crushing the olives. When he considered that the paste was quite homogeneous he would stuff the scourtins with it and stack them under the presses nestled in the stone alcoves. Arnéodo then changed the direction of the transmission belts and, still thanks to the force produced by the paddle wheel, the presses slowly descended, crushing the cakes and their contents. The oil flowed like a river of gold along the stacks of scourtins and fell into the large vats full of water. The recovery work really began under the suspicious eye of the peasants.

The first press, the cold press, gave the virgin oil with a beautiful bright color and its incomparable scent filled the mill.

There was still a lot of oil in the paste. Arnéodo kneaded it in the scourtins with hot water and pressed again. The oil obtained on the second pass was a little greener, a little more acidic, but still quite edible.

As payment for his work, the miller kept a tenth of the oil pressed in the main mill, so the peasants attended the pressing until the end to check that the accounts were respected.

The miller also kept for himself all the oil processed in the other mill and the residual products.

In the second mill, oil called ressence was produced, very thick and acidic, intended for refineries. It took no less than two additional pressings to finally produce a product that looked like engine oil, and which after treatment was used in soap factories or transformed into cakes by fertilizer manufacturers. This last work was called "hell".

All this work was hard and thankless, but profitable. It took no less than four pressings, each time boiling the paste, to extract everything that could be extracted mechanically.

At the end of these successive operations, all that was left at the mill was the broken olive pits and there was no oil. We called that the pomace. Do you know what I did with this pomace? Well, I heated myself with it. Admit that at that time, we were real environmentalists!

The atmosphere in the main mill was unforgettable.

First there was the roar of the water falling on the blades, the cracking of the pits crushed by the stone, the friction of the belts, the hissing of the presses. And then there was the steam emanating from the boiler and the sweating bodies and above all this incomparable scent of crushed olives as if all the good smells of Provence had entered the mill.

When a pressing was finished, there was always someone to grill, on a fire of vine shoots or pomace, slices of large bread which were then rubbed with garlic and soaked in virgin oil coming out of the press.

These toasts were accompanied by red or rosé wine and as the work was hard, these watered breaks were welcome.

During the olive season, the mill was open every day and, often on Sundays, hunters brought thrushes, threaded them on skewers and grilled them on the vine shoots, not forgetting to add twigs of farigoule and rosemary to the fire. The toasts received the perfumed juice of the birds; a real treat. On those days, with the help of the rosé wine, there was a joyful animation in the mill and even the taciturn Arnéodo had a smile.

Thanks to Arnéodo's advice and explanations, I was able to recognize the best varieties and the best olive vintages quite quickly. As with wine,

the terroir is very important and the oil is all the more fruity when the olive trees grow on the sunny side of the Cabris or Cotignac hillsides.

After a month of learning, under the orders of my worker, I decided to take the plunge. I went to buy olives to complete the mill's custom work. The discussions were tense and the farmers who intended to get the best price for their harvests, naturally tried to take advantage of my inexperience and my youth; for a start I was not doing too badly. The day I understood that the olive was a real wealth for the Provençaux, it was after having negotiated with a good widow, who lived in the charming village of Entrecasteaux, the purchase of her production. She had a reputation for having high-quality olives and, although a widow and old, she knew perfectly well how to defend her interests. On seeing a sample that she had shown me, while offering me a small glass of walnut wine from her production, we agreed on the price. So I asked her where I could load the olives. The good lady took me to her room; she slept on her olives like a miser on his money.

At the end of February the mill closed its doors. The season's results were good and I felt that I could start producing melons while waiting for the apple trees, which I had decided to plant thanks to the vine uprooting premium, to come into production.

Arnéodo was also happy, because in addition to the agreed salary, I had interested him in the turnover and, above all, he had seen that I had kept my word by letting him run the mill as he pleased.

Once the apple trees were planted with Arnéodo's help, I dug straight mounds between the fruit trees to receive the melon seeds. At the end of April, we sowed the Charente cantaloupes.

In Fayence, when I first arrived, people watched with mocking curiosity as this Parisian, this son of a bourgeois, struggled to clear the fields of stones and pull up the mulberry trees, but it turned into a real laugh when the neighbors learned that I wanted to plant melons.

– Melons here, the Parisian is crazy, we should leave that to the “genses” of Cavaillon –

Everyone waited with sadistic impatience for the moment when failure would be obvious and even Father Arnéodo who was no more convinced than the others, worked reluctantly and could not stand the comments of passers-by who stopped when they saw him working in the field.

“Oh Arnéodo, your melons are not yet ripe, do you think you will be able to taste them before the next olives, are you planting Cavaillon or Parisian?”

Fifteen days after sowing, a time that seemed interminable to me, the earth swelled then cracked and the first cotyledons appeared. The emergence was uniform. After that it went very quickly. The well-cared for and well-watered plants grew quickly and soon large, beautiful dark green leaves covered and spread out all the mounds.

From May to July, Arnéodo and I spent most of our time sulphuring the plants to combat powdery mildew, pinching and watering the long rows that were a hundred meters long. The pinching, which had to be done frequently to encourage the fruit to thicken, was backbreaking work that kept your back bent for hours on end, but what was most exhausting were the night-time irrigation sessions.

According to the agreements made with the residents of the Camandre, I was only allowed to use the water once a week from eight in the evening until seven the next morning.

Since irrigation was done by gravity, it was necessary to wait for the water brought by channels drawn at the foot of the mounds to reach the end of each row before moving on to the next one.

Equipped with hoes and electric torches, we spent the night directing and monitoring the proper flow of water, but from time to time, I did the work alone to spare Father Arnéodo who was no longer young. I had developed a technique to rest. I had calculated that for the water to reach the end of the row without flooding it, it was necessary to change rows about twenty meters before the end. I lay down on the ground with one hand in the irrigation channel. The cold water reaching my hand woke me up and I just had time to rush to the beginning of the field to change rows and start the maneuver again. Sometimes the water came out of its channel and it was not the contact on my hand, but on my wet back that woke me up.

The fruits grew visibly and the field was covered by small round balls that protruded from the leaves.

On the first of August, I will always remember it, I found the first ripe melon. It was very round with a pretty golden color, the well-defined slices were separated by blueish indentations. The stalk slightly cracked at the joint of the fruit, let out a drop of sap red as a ruby. The moment of truth had arrived! Arnéodo lent me the Opinel that never left his pocket. With a slightly trembling hand I handed him the first slice of our first melon. The flesh had a beautiful orange color and the scent that came from it was pleasant.

After spitting out his corn paper butt and removing the seeds, he bit into the fruit with gusto. "So?" So he didn't answer me, handed me the half-eaten fruit and smiled. Very fragrant, both firm and melting, the fruit was full of sugar and sunshine. It was a success. Then everything happened one after the other. At seven in the morning the harvest began.

I selected the ripe fruit, delicately cut the stalks so that they would remain attached to the melons. Arnéodo followed with the tractor and loaded the cantaloupes into the trailer then brought them to the garage transformed into a packing room. I had hired two young girls from the village. They worked from nine to noon and, after the sacrosanct siesta, from four to seven. Under my instructions, they sorted, calibrated and wrapped the melons in pretty, slightly ochre paper and put them in crates filled with frison. Their last job was to stick next to the peduncle a pretty label reminiscent of the leaf of the plant and on which was written in gold letters and in relief "Moulin de Camandoule". Then, after the girls had left and had eaten dinner, we weighed and loaded the melons into the van. At three o'clock the next morning I left for Nice to deliver my load to the Pallion market.

When I delivered to Cannes I left an hour later. At first the sale had been difficult because the brand was not known, and then it was the high season, when the merchandise is plentiful, but quickly the buyers asked for Moulin de Camandoule because these melons with firm and fragrant flesh and consistent quality were appreciated.

The chef of the Palm-Beach had even asked the broker of Cannes to reserve his best crates for him. I liked, once the van was unloaded, to stroll a little on the market, especially the one in Nice. I discovered there, in the small bistros that line the Paillon, the tripe Provençal style. Believe me, and you know that you can trust me when it comes to food, the tripe is cooked in a spicy tomato sauce that you sprinkle generously with Parmigiano Regiano At six o'clock in the morning, it is a real treat. The harvest lasted until September 15. I slept during this period no more than four hours a day. I finished this season exhausted but delighted because I had produced forty tons of melons, but especially because the people of Fayence came to buy them directly from the mill. "After all, the Parisian is not that crazy and besides, by Jove, he really worked hard."

For three years I lived a dream life at the mill, and then one day, in a few hours, it was a disaster.

In the middle of the night, snow fell non-stop on the Var. In the memory of the Provençals, we had never seen that. When the snow stopped, it was the cold that arrived, the thermometer dropped to minus fifteen. It only takes a few hours to freeze all the olive trees in the Var. Oh, it was not a simple frost destroying a harvest and from which we recover! This one struck at the heart, killing the olive trees, wonders of nature that Cézanne loved to paint so much.

The farmers of the Var lost their main source of income and the mills were forced to close for lack of olives to crush.

One morning I saw Arnéodo, a suitcase in his hand. I expected it.

For the first time that we “lived together” I felt him embarrassed.

“You know the mill without the olives! »

«I understand»

I paid him his salary. He picked up his suitcase and walked slowly towards the door

«Arnéodo» He stopped and turned around slowly.

«I will miss you.»

For a moment, I thought I saw his blue eyes cloud over and his corn paper butt tremble.

When I write this story to you fifty years later, I know that I will never again smell that incomparable odor of virgin oil, I know that I will never again see that river of gold cascading along the scourtins, ;

I know that I will always miss the Moulin de la Camandoule.

M.C.